In the era of online social media, network contagion effects allow social causes to reach a large number of interconnected individuals fast, efficiently, and at low cost. Some social causes go viral and garner significant support very quickly; others are less successful. Understanding the nature of viral altruism and its core behavioural characteristics can help us sustain positive social change.

Social causes go viral

A prime example of the value of ‘social contagion’ effects is illustrated by the 2014 ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which went into history as one of the largest and most successful online viral social causes. The campaign itself is simple; participants are challenged to upload a video within 24 hours in which they pour a bucket of ice cold water over their head, mention amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in the video, make a charitable donation in support of its cause and nominate others to do the same.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Over 28 million people joined the challenge and millions of videos were viewed in excess of 10 billion times by approximately 440 million people worldwide1. The viral nature of the campaign earned the national ALS Association, an organization which raises public awareness and funding for ALS, an additional US$115 million1.

Social cause websites now have the ability to connect and mobilize over 1 billion Facebook users to action on specific social issues. A successful example of this is the Save Darfur movement on Facebook, an anti-genocide campaign that rapidly grew into one of the largest online social movements2. Another key example is the Facebook organ donor initiative, which allows Facebook users to officially register and declare themselves an organ donor as part of their online profile. The campaign went viral and resulted in nearly 40,000 new online registrations in just two weeks3.

Collectively, I refer to this trend as viral altruism; the altruistic act of one individual directly inspires another, spreading rapidly like a contagion across a network of interconnected individuals.

SMART campaigns

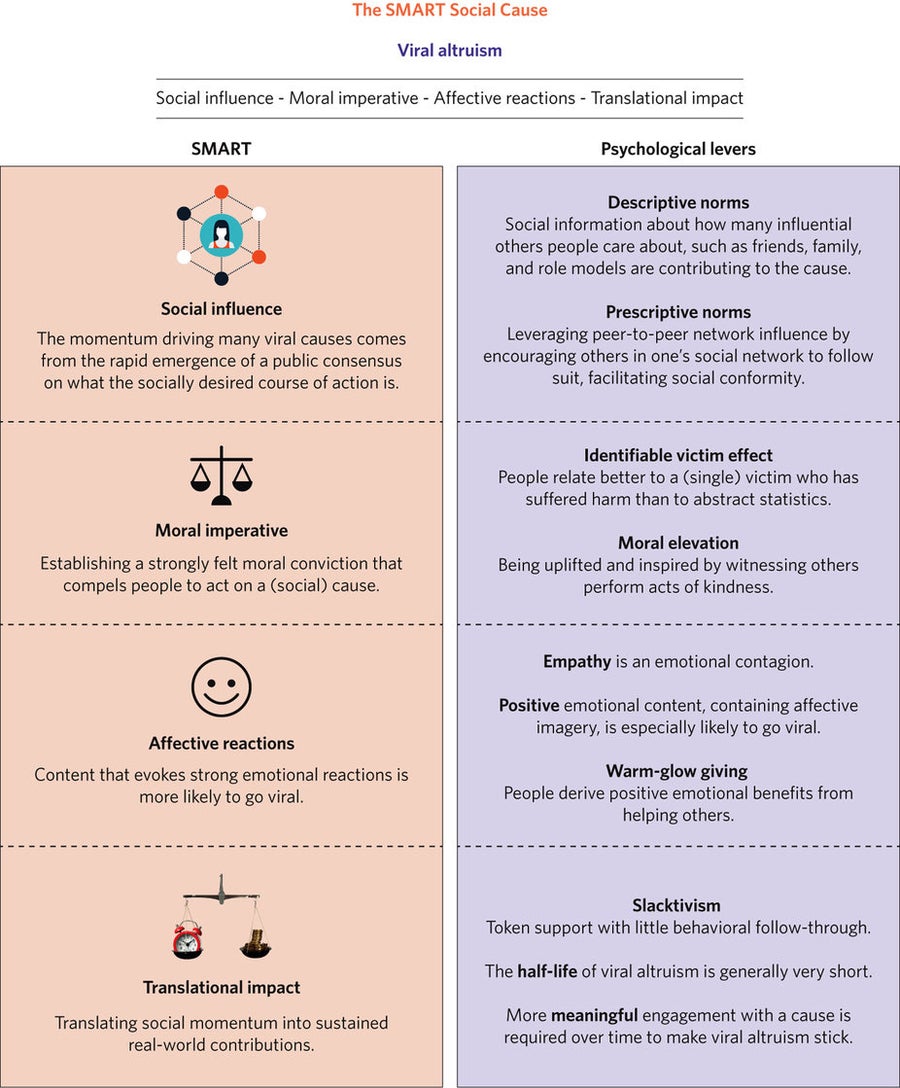

Although each cause is different in its focus, some of the initial success of popular viral social cause campaigns can be explained by what they have in common: their implicit reliance on a number of well-established psychological levers, which I will refer to as the SMART criteria, where SMART is an acronym for campaigns that successfully leverage social (S) influence processes, establish a moral (M) imperative to act, inspire (positive) affective reactions (AR), and are able to translate (T) and convert social momentum into sustained real-world contributions. (FIG 1)

For example, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge was largely centred around publicly challenging peers in one's social network to join the cause. Similarly, the Facebook organ donor initiative visibly shared new online registrations to all friends in an individual's network3, encouraging social conformity.

In addition to social influence, many successful campaigns present people with a clear and strong moral motivation to act on a social cause, from stopping mass genocide, to finding cures for debilitating diseases, to helping to save the planet.

Moreover, content which evokes strong positive emotional reactions is more likely to go viral4. Indeed, many viral social cause campaigns specifically use emotional content that elicits empathy, compassion, or outrage, such as people suffering from disease (for example, ALS), victims of war (for example, children), or protests against social injustice.

Ultimately, the key challenge for most social cause campaigns is deciphering how awareness and social momentum can be translated into sustained real-world actions and behaviour. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, which received over US$115 million during its initial launch in 2014, is a prominent example. Yet, although the unprecedented viral nature of the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge captured the attention of the general public, scientists and policymakers alike, to what extent did its success persist over time?

Failure to replicate

While the campaign was relaunched in 2015 and has served as a blueprint for the design of similar social charity campaigns hoping to go viral, its success has not been replicated, raising only 0.9% of 2014's campaign earnings in 20151. Nonetheless, improving our understanding of viral social campaigns, social tipping points, and perhaps most importantly, how to sustain their momentum, is crucial for continuing to address critical global societal challenges, such as poverty, climate change, global health, and terrorism. In fact, evaluating the success of viral campaigns such as the Ice Bucket Challenge will help illuminate an important larger lesson about the dynamics of societal altruism and prosocial giving.

The half-life of viral altruism

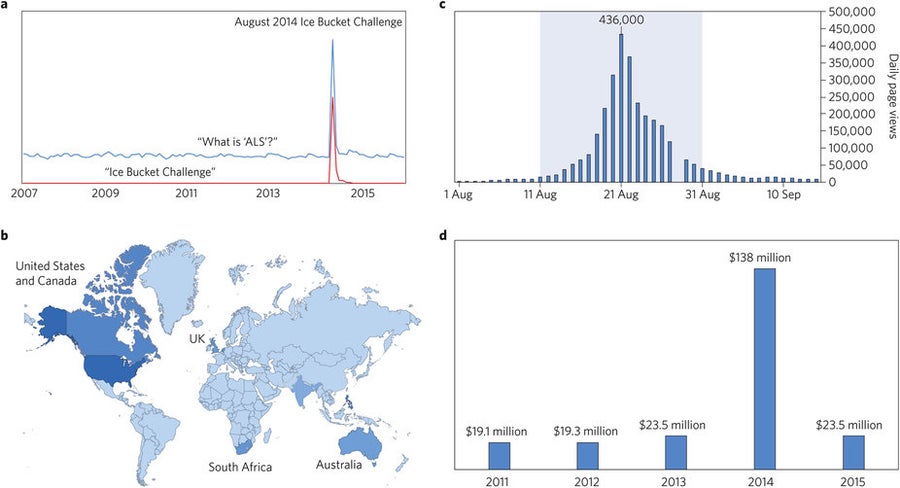

By analysing a number of key public interest indicators both before and after the ALS campaign was launched in August of 2014, I illustrate that the general profile of the campaign seems to bear out the old adage; “a flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long”.

a, The graph was generated using the Google Trends tool and represents total search traffic for the terms “Ice Bucket Challenge” and “What is ALS?” relative to the total number of Google searches as a whole over time, indexed and normalized (https://goo.gl/wcwwPH). Similar trends are observed for related terms (for example, “Lou Gehrig” or “Motor neuron disease”). b, The map plots the relative search volume geographically by regional interest. Darker blue shades reflect higher regional interest. c, The graph was generated using the Wikipedia page view statistics tool and shows page views for the main ALS Wikipedia page leading up to, during (indicated by the shaded region) and after the campaign in August 2014 (http://go.nature.com/2jVojyP). Daily page views peaked at 436,000 during the campaign. Page view statistics for 28 August are missing. d, The graph shows the total annual contributions (US$) from donations to the national ALS Association based on public returns of the Internal Revenue Service Form 990. Credit: Nature, Feb 13 2017, ISSN 2397-3374 (online)

Google searches for popular ALS phrases were generally infrequent but showed a dramatic spike during the campaign in August 2014, yet this momentum was not sustained as search activity quickly dialled down to previous levels after the campaign ended. A similar pattern is observed for visits to the main ALS Wikipedia page as well as for total funding to the ALS Association, which, despite a relaunch of the Ice Bucket Challenge in 2015, fell back to its pre-campaign levels. In fact, the ‘heartbeat’ of the campaign flatlined entirely after its peak in 2014.

Thus, although the campaign successfully raised a commendable amount of one-off donations to help fund important future research for ALS treatment and care services, it is questionable whether the campaign did anything to substantially improve people's understanding of serious neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS, or foster any type of sustained long-term support for its cause. Indeed, estimates suggest that 1 in 4 participants did not even mention ALS in their videos and only 1 in 5 participants mentioned a donation5.

These effects are not unique to the ALS campaign. For example, the Facebook organ donor initiative elicited more than 60% of its total online registrations in the first two days, after which the number of new sign-ups decayed quickly3. The Save Darfur cause generated most of its members in the first few months and a more detailed analysis revealed that after the initial act of joining, 72% of members never recruited anyone else and the majority of members never donated2. Similarly, energy conservation competitions have been shown to generate significant social momentum during the campaign but fail to sustain behavioural conformity in the long-term6.

Why viral campaigns are so short-lived

One primary behavioural scientific explanation for the notably short half-life of these types of viral campaign is that they mainly leverage ‘extrinsic’ incentives to do ‘good’, rather than cultivating an internally sourced ‘intrinsic’ motivation to help others. This is important, as behavioural research has shown that (unconditional) intrinsic motivation often sustains helping behaviour in the long-term, whereas (conditional) extrinsic incentives only tend to work for as long as the social incentive is maintained — of which a 4-week (summer) challenge is a prime example6. Once the social tipping point of a campaign has passed, momentum can decay quickly. In fact, extrinsic incentives, such as competitions, can actually undermine people's intrinsic motivation to do good by eroding moral sentiment7. For example, motivation to participate is most likely sourced from a desire to ‘win’ a challenge rather than caring about the cause itself.

Sustaining viral altruism

A key question for behavioural scientists, policymakers, and practitioners alike is what factors determine whether a social cause turns out to be a one-time fad, or a reliable and sustained source of public support? For some urgent societal challenges, such as climate change, the problem may lie in generating social momentum to begin with. However, even for those social causes that have gone viral, the half-life of viral altruism is typically very brief.

Many viral campaigns draw their success from the psychology of ‘consensus’. To illustrate, once a social tipping point has been reached (for example, one million views or shares), the appeal of the social consensus itself becomes a self-perpetuating mechanism. This can be problematic for two key reasons, namely; (1) it elicits relatively superficial engagement with the cause, and (2) the exponential increase in social momentum is unlikely to be sustained, as explosive unchecked positive growth typically results in system collapse. Indeed, the Ice Bucket Challenge, organ donor and Save Darfur campaigns all started out viral before they plummeted. Increasing the longevity of viral altruism may therefore require more meaningful engagement with a social cause, and paradoxically, slowing the viral nature of the campaign. Deeper engagement seems especially vital, as something as simple as a single phrase connecting a campaign to its cause can make a difference. For example, one analysis reported that those who mentioned ALS in their Ice Bucket Challenge video were five times more likely to donate than those who did not5.

The No-Shave Movember movement, which encourages men to grow out their facial hair to help raise awareness for men's health issues, may be a successful example. The foundation claims that its 2014 campaign resulted in over 2.3 billion conversations, with 75% of participants becoming more aware of health issues facing men, and 6 out of 10 members reporting to have sought out medical advice8. An important characteristic of the Movember campaign is that although it quickly gained local popularity, it did not experience the same type of viral hypergrowth. The campaign was founded in 2003 by 30 people with AU$54,000 in donations and has grown more steadily over the last 10 years to about 5 million global members, raising AU$136 million in 2014 with an average annual growth rate of over 100% (ref. 8). Thus, the Movember campaign has been able to translate social conversations into sustained donations over time.

One reason for its sustained success may be that the movement is framed around a recurring yearly event rather than completion of a single action or behaviour. Moreover, the incentive seems to be intrinsic, as it allows members to define their identity as part of a larger social movement.

In competing for the public's rapidly shifting attention span, mobilizing audiences to large-scale collective action is a daunting task. Viral social campaigns can effectively capture the attention and support of mass audiences, but in order to make viral altruism stick, more gradual and deeper engagement with a social cause is required over a sustained period of time.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on February 13, 2017.